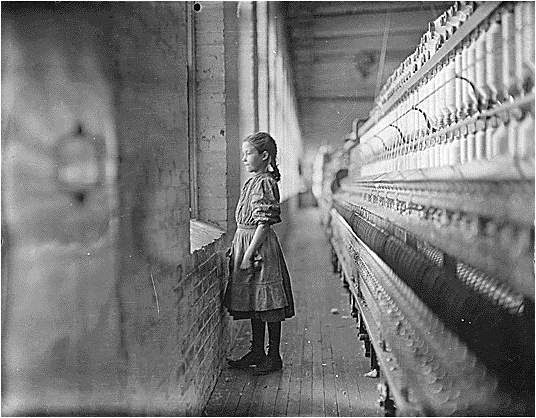

THE GIRL AT THE WINDOW

Lewis Hines' photograph of a child worker in the spinning room at the Cherryville Mill, NC,early 20th c.

I heard the historian Steven Hahn pose the big post-modern question about history in this way:

“What is knowable about history? What cannot be known?”

I think that is the post-modern question about human existence, as well, and maybe we are all talking about the same thing, since history is human beings mostly trying to find better ways to live while they persevere through the lives they’ve been given. Even my English students. History is human beings taking risks and suffering and striving and, once in a great while, triumphing.

But here’s the important thing that often gets overlooked, and which I wish I could make clear to Mallory: there is no history at all, no defeats and no triumphs, unless someone is telling the story.

#####

Supervisor's house at Glencoe Mills, restored mill village in Burlington NC

Summer ends officially for me with the start of classes on August 18. With money and reliable transportation an issue this year (anyone who is trying to pay the bills as ‘contingent’ college faculty knows what I’m talking about), my husband and I stayed mostly close to home this summer, exploring the historical byways of South and North Carolina, as I’ve documented in previous entries.

Perhaps because I’ve lately toured so many down-at-heel mill towns and farming communities, and because I am constantly trying to retool my strategies for teaching students who have spent their lives in these communities, I’ve been thinking back to the National Endowment for the Humanities seminar I attended in Elon, North Carolina, four summers ago, during which we studied the cultural and economic factors that produced the ‘New’ South. I wrote a paper as my final presentation for that seminar that I have been rereading in preparation for going back into the classroom. That essay, in which I tried to articulate the insights I gained after partaking of some extraordinary lectures and field trips offered by that week-long examination into how the Carolina Piedmont developed as it did, has reminded me of just how challenging my job is, and also, how rewarding. This is what I wrote:

The Girl at the Window

Working, writing and curing hams as if your life depended on it; reflections on survival in the Carolina Textile-Mill Belt

I am thinking about pigs and windows. The windows I will explain, in a bit. That I am thinking about pigs is not surprising because I am eating a chopped pork sandwich and studying the barbecue restaurant’s napkins and tee-shirts depicting happy hogs (and why would the hogs be happy, anyway?), but even if I were not eating barbecue I would probably have pigs on the mind because I am in central North Carolina where pork is paramount.

Mill houses at Glencoe

I lived here once, sixteen years ago, and when I first encountered this place it was so foreign from everything I had ever experienced up until then in the cool, sophisticated, tolerant, Buddhist-leaning, vegetarian Lotusland where my husband and I had been raised that we turned to one another back in that time, we joined hands, and we leapt into it like joyous human sacrifices leaping into a flaming caldera, while our loved ones stood on the rim and screamed as we descended. Even our seven year-old embraced it, when she stood and looked up at the giant trees that didn’t seem to end and looked down at the turtles in the sleepy creek and the house with the crooked roof and asked, “Is this Heaven?”

We went somewhere to eat and the waitress asked us where we wanted to sit and we said “non-smoking section, please.” She raised her eyebrows which is what passes for a laugh in these parts and she put us at a table downwind of four men eating fried liver mush and smoking cigars. We laughed almost hysterically, because we were truly happy, and there is no laughter more releasing than that, when you laugh because you are happy and you did not realize until that moment that you were unhappy.

The Garrett Farm, early 19th c., Alamance County, NC

We were happy to be taking a crazy risk to live in a place that we didn’t understand. Maybe we thought we were following in the footsteps of our reckless progenitors, who were forever moving beyond the charted territories of respectability and common sense, who were forever ‘betting on the come.’ Or maybe we were willing to take that leap because living somewhere where people talk and eat and think and live differently from what you are used to can shake your moorings enough to make a new view possible – a new way of ‘seeing.’ This is the kind of miraculous window that some people (like me, I’ve discovered) live for. I looked through this window when I was four or five years old and lay naked except for my dish-towel loincloth, crowded in the teepee in the backyard with my three sisters who were also wearing dish-towels (we weren’t really gender-confused; but my oldest sister had caught on to the fact that braves had more privileges in the tribe than squaws, and we were young enough to think we could opt out of being female if we dressed the part). So I lay looking up through the smoke-flap at the Milky Way and asked the stars, “Is this how it was for the first people – was everything this bright and quiet? Did they fit into the world this way, like they belonged here, like they were all tiny leaves on a very big tree?”

Cat at Glencoe Mills

That is history for me. It is a window that opens. The window doesn’t provide answers; it just shows you the complicated reality. Sometimes it is a window that flashes past you, as if you’re speeding by it on a train. But when you’re lucky, like when you are deep in South Carolina outside Woodruff or Cowpens and you walk into a bait-shop in hopes of coffee, and there are two men lounging by the register in mechanic’s overalls and one of them turns to look at you, and he has a sunburned face as hard as a manhole cover with ice-blue eyes and a wary thin mouth and you saw this face just a few days earlier in a Matthew Brady photograph of Confederate prisoners and in those few long moments when you look at him before it starts to get a little weird for everyone, the window sash is raised, and what you see through that window takes your breath away.

Child's bed made by Thomas Day in the 1860s, free African-American carpenter, NC

It is not the same as seeing actors dressed up as people from the past, although reenactments are a goofy pleasure in a class by themselves. ‘Seeing’ history is not about seeing an imitation of what happened in the past; it is about ‘knowing’ what happened in the past in your heart and your gut and your solar plexus and your collective unconscious all at the same time. It is like walking through the Holocaust Museum in D.C. and seeing the shoes. If you have been to that museum, all you need to say to one another is ‘the shoes.’ And then you will have to sit down, or swallow the lump, or duck behind a door and have a little cry. Because when you see the shoes, or remember seeing the shoes, you ‘know.’ That is the excoriating experience of understanding history.

So that is why I am thinking about windows and also about pigs. And thinking about pigs makes me think about my English students, but perhaps not for the reasons you suspect.

I am seeing that raw lump of pork in the wooden bowl on the table outside the smokehouse at the 300 year-old Garrett farm in Alamance County, and the sunny man from West Virginia missing most of his teeth who explained that the pork would typically be rubbed in ashes to discourage maggots, or, as he put it, to “keep the critters from kissin’ on it.”

And I am reading from the sign about the many lengthy steps that were required to turn the hind-quarter of a hog into an edible smoked ham in 1835. It could take up to nine months, as long as human gestation.

If I want to serve a ham at a dinner party (which is problematic because a significant number of people I know and who would accept an invitation to my house for dinner, even people born and raised in the Carolinas, do not eat meat, or they eat it selectively, eschewing pork or beef and favoring chicken or perhaps limiting their flesh intake to fish, so long as the face has been removed). But. If I want to serve ham I drive to Charlotte or to Spartanburg and head for a high-end supermarket. I buy a processed ham and bring it home and cook it and that is all. I do not have to chase after a terrified, 200-pound hog who shrieks for mercy as he batters the rails of his pen trying to dodge my sharpened ax. I do not have to bludgeon him senseless with the ax handle and hoist him on a rope by his hind feet above a vat where I slit his throat and let him bleed out.

Garrett farmyard

And it is suddenly quite clear to me that I am expecting the impossible from my students when I expect them to know how to create meaningful, coherent, well-researched essays in fifteen weeks, each one constructed painstakingly, step by complicated step – from invention to discovery to research to analysis to synthesis to first draft to revision to final draft.

Like me, none of my students (or very few, although one or two have been to war, and I recognize that they’re different…) but few of my students have ever had to make or build or cook or plant something as if their lives depended on it, whereas the lives of our ancestors depended on their doing these things, and since they were our ancestors, they did them correctly.

What I see is that my students don’t understand why they should have to slaughter a hog on a cold day in late autumn and cut it up and rub the hind-quarter in molasses, cayenne and salt and throw it in a cold hearth and get it good and sooty and then hang it in a smokehouse over a smoldering fire that never goes out and check it and poke it and cut the mold off and before it starts to go bad from the heat in spring, cut it down and bring it into the house and start all over with the rubbing and sprinkling, and then cook it over a good flame for a day or so and finally, finally, yell for all seventeen children and the in-laws and the one-legged husband to come running and eat the damn thing.

My students and I can simply go to the store and buy one already baked and even sliced, and we can run it home in twenty minutes and eat it in front of the television with our cats beside us nibbling on the scraps. And in eating it, we give no more thought to the life lived by the pig who provided our meal than we give to gravity, or relativity, or other mostly incomprehensible conditions of existence.

The Pacolet River at Pacolet Mills, South Carolina

In other words, my students must wonder why Ms. Rivers goes on and on about the necessity of constructing a meaningful essay in one’s own words when they can push a button on the keyboard and watch Google spit out the choices and then they push another button and Wikipedia disgorges some paragraphs which they don’t really see any reason to read because they contain the assigned keywords, “financial meltdown,” “intelligent design,” “gay marriage;” and then they push another button and download the paragraphs into a Word file, and they do this a couple of times, and then they type their names and the date at the top of the paragraphs and print the pages and then they’re free to download the latest Rihanna video while they’re online and then a couple of things on YouTube and then they check Facebook and give a couple of shout-outs to their friends and they feel like they’ve really slogged away at their homework.

But here’s the thing. And this is why I’m thinking about happy pigs. Because if there’s one thing I’ve noticed about my students, it’s that they don’t seem all that happy. I realize they would probably be much happier if they weren’t in English class, but I’m really talking about another kind of happy. I mean the kind of happy where you know, and feel, that you belong in the world, like you are a tiny leaf on a very big tree.

Shagbark hickory, Garrett Farm

This ‘knowing’ kind of happiness opens a window on the past and you see through it and understand how you are connected to what came before and you see the path that will carry you into the future. I suppose this is hope, as much as it is happiness. My students are mostly still quite young, but they don’t seem hopeful. Maybe this is because they already know everything there is to know, and so what is there left to discover? What is there to work for? Or maybe they’re just afraid.

One girl, "Mallory," sat through the entire spring semester last year without smiling once. It became a challenge to me, getting her to smile. I saw her mouth make a crooked movement upwards one morning, when she was working in a group and a boy said something funny to her. But for me, she won’t smile. I drag out all my rusty grammar jokes and adverb puns (yes, there are such things: “I’m going off to kill Dracula,’ declared Tom painstakingly’”…) and my favorite story about the rule of prepositions:

"Mallory," I said, looking straight at her. "A blonde and a brunette walk into a bar. Brunette says to the blonde, ‘Where’s your birthday party at?’ Blonde says to the brunette, ‘You must never end a sentence with a preposition.’ Brunette says to the blonde, ‘Where’s your birthday party at, BITCH?’"

The other students laugh, covering their mouths with their hands; it is Schopenhauer’s ‘sudden perception of incongruity’ exemplified. But Mallory is determined not to laugh, not even to smile. It is because she has to show me that this class has no value for her. She works nights in a nursing home in Gaffney; she has a troubled family down in Pacolet. The girl is just trying to get a certificate to be a medical transcriptionist and then she will be soooo gone from this school; she does not care what a syllogism is and it makes no difference to her if we are reading the Declaration of Independence or Mein Kampf, it is one and the same. Every day she comes to my class tired and stressed and angry, and she does not see what there is to be happy about.

Original cabin at Garrett Farm

Somehow, I must convince Mallory to slaughter a pig. If she were to hoist her imagination on a pulley and let the ideas pour out where she could look at them… if she took time to let the message rot and reek and turn different colors and then she shaved off parts here and there and finally determined that it was ready for consumption… and if she served up this thing that she had made, from scratch, by herself, as if her life depended on it, I believe she would feel better about herself. She would feel capable. And yes, perhaps, she would start to be happier.

Maybe the key to this lies in getting Mallory to see that she has a history, that many dead ancestors struggled to put her on this earth and would want her to exult in who she is and to test the limits of what she could yet be.

I think about telling Mallory that in a file drawer in the National Archives in Washington there is a photograph of her great-grandmother when she was ten years old. She seems to be wearing an older brother’s shoes and she is painfully small for her age; her shoulders and the dark braid down her back are frosted with lint from the alley of cotton-threaded spindles that stretches into the distance behind her. For just a moment, the girl turns her back on the spinning room and the rest of the Cherryville mill and in that moment the photographer Lewis Hine captures her looking out the window at the bright world from which she’s been exiled. She is like Persephone longing to be carried out of the underworld into the sunshine, like a Cherokee child behind a reservation fence, or a black sharecropper’s son strapped into a sack of cotton bigger than he is. But Mallory will never see this photo of her great-grandmother at the window. She doesn’t know that the little girl’s job was spinning in the mill for twelve hours a day, six days a week, at 75 cents per day, but that her work was her: Mallory. Locked in the spinning room, the child was saving her own descendants from a hard life of suffering with her life of exile and toil and pellagra, like a little boddhisatva. Like a lint-covered Christ.

I heard the historian Steven Hahn frame the big post-modern question about history in this way: What is knowable about history? What cannot be known? I think this is the post-modern question about human beings, as well, and maybe we are all talking about the same thing, since history consists of human beings making decisions and mostly living their lives in the best way they can. Even my English students. History is human beings taking risks and suffering and trying to survive. But here's the important point that often gets overlooked, which I wish I could make clear to Mallory: there is no history at all, great or small, without someone telling the story.

###

Photograph by Lewis Hine, early 20th c., of child worker in Cherryville mill, NC